Constantino Medina was born on the eve of the feast day of St. Helena of Constantinople, thus his name. He was also called Tinoy and Ante. Tinoy grew up in the coastal town of Hagonoy, in a barangay called Sagrada Familia, where poems can be plucked off the air just by the way people speak. His father was a fishpond caretaker while his mother looked after the couple’s six children.

Tinoy’s early life was like most everyone else’s in Hagonoy, a fisherman’s life. Even as a young boy, he fished in the sea, repaired footpaths and levees in fish ponds, and gathered seaweeds in Manila Bay to sell to gelatin makers. He was hardworking and industrious, but quiet and unassuming. He liked reading and had a quick, inquisitive mind. Friends say he could have become a lawyer.

In the late 1970s, Bulacan produced a number of nationalist and progressive writers and artists, such as a group called Galian sa Arte at Tula (GAT). These artists would sometimes bring their barriomates, Tinoy among them, to watch for free some of the plays staged by the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA) in Manila.

The PETA plays Tinoy saw woke him up to realities in Philippine society and started his political awakening. When he heard that a protest rally was being scheduled in Manila, Tinoy and some of his townmates would plan to join these protests. He was joining more and more political meetings, taking him away from home for long periods of time. He was the fifth in the group of organizers that was formed to start the seeds of Bulacan’s AMGL.

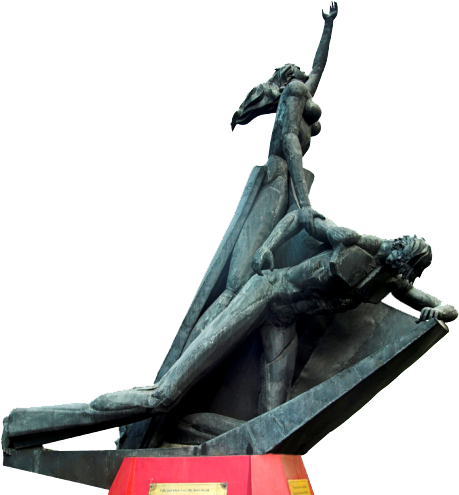

The Bulacan Martyrs

While most ordinary Filipinos were cowed by the repressive machinations of the Marcos dictatorship, a good number actually exhorted the population to defy the regime and struggle to reclaim their freedoms and see democracy restored in the country. Most of these courageous few came from the youth sector.

The youth had the advantage of exuberance, idealism, and a deep sense of love for country. They, particularly the students in schools, also had access to information and resources useful for understanding the situation the country was in. It was natural that the youth would be the least cowed by the dictatorship.

Testing the martial law waters, first they organized to demand reforms in the campuses, raising issues such as tuition fee increases and demanding the restoration of student councils and student publications. Then they spread out into the communities and the rural areas, where they engaged the rest of the working population in discussions and debates, seeking to sweep away apathy and fear, and bolster the people’s courage to fight for justice and freedom. In doing this, these young people often had to abandon lives of comfort and ease, risking discovery, arrest, jail, even death, for some higher purpose. Many survived these risky ventures but some did not. They fell on the wayside, never returning to their old lives or their waiting families, their bloods merging with the soil where they fell.

Among these young people who heeded this powerful call to give all for one’s country despite the risks, never to return and never even to see victory, are the five youths from Bulacan province being nominated for Bantayog’s roster of heroes and martyrs: Danilo Aguirre, Edwin Borlongan, Teresita LLorente, Renato Manimbo, and Constantino Medina.

Circumstances of Death

The group had been meeting to draft a program of action and to evaluate their initial work. Just this early stage had taken months to do. Then, one day in June of 1982, they were meeting inside a farmer’s house in Pulilan town when a huge group of soldiers came and took them away. The following day, all five were found dead.

A factsheet from the Task Force Detainees of the Philippines (July 9, 1982) later gave an account of the incident:

They were six organizers, including a female, meeting at a farmer’s house to assess their work when suddenly they heard orders “not to move” for the house was surrounded. Then emerged some 30 heavily-armed soldiers from the 175th Philippine Constabulary (PC) Company led by a captain and a major. One of the six organizers inside the house managed to climb out of a window undetected and hide himself on the rooftop. The rest of the unarmed organizers submitted themselves without resistance.

Early the following morning, townspeople of San Rafael, some 20 kilometers away, were shocked to see five bullet-riddled bodies displayed at a corner of their municipal hall. Casualties from an encounter, the PC soldiers said. The municipal hall employees shelled out personal money to buy caskets, and for the female who was clad in pajamas, a pair of jeans. They had the bodies buried at the local cemetery in the afternoon of that same day.

The sixth member, still unaware of his friends’ fate, quickly told the victims’ families what had happened. Relatives immediately went to inquire at the camp of the 175th PC Company as well as in other possible military centers, but they were told no such detainees were being held in their camp. They learned of the deaths the following day.

The families of Rey Manimbo and Edwin Borlongan recovered their bodies on the third day. Those of the three others were recovered ten days after the incident, but only with the intercession with the military of the Bishop of Malolos. The bodies of all five showed heavy bruises and many bullet wounds.

Impact

Nine priests offered to concelebrate a funeral mass for the last three bodies to be recovered. The mass was said at the Barasoain Church in Malolos, after which the bodies were buried at the Meycauayan Cemetery. A campaign was started in Bulacan among various church and human rights groups to press for justice for the five youths. When Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. was himself assassinated a year later, many Bulakeños joined the protests, remembering the five unarmed youths whose lives were so harshly snuffed out the year before. Many poems, songs and stories would be written in memory of the five organizers. The AMGL itself began to take root in Bulacan. The perpetrators were not known to have been investigated nor punished.